In a tight housing market like the Bay Area, a particular demographic prefers small, private accommodations to large, shared accommodations. Members of the urban workforce – teachers, nurses and paramedics – seek private and high-quality housing within their price range and are thus willing to trade size for a well-located, comfortable, and private housing product.

Unfortunately, such a housing type does not exist en masse. A severe mismatch between housing needs of middle-income professionals and the availability of affordable, functional accommodations has led to a trending increase in unmarried young adults living with their parents and other housemates. If housing that suited their budgets and needs were in reach, it is doubtful that this demographic would choose to live in such arrangements.

To answer the question “who would want to live in less than 400 square feet?”, it is critical to understand the changing landscape of American demographics. Age, occupational trends, and the changing dynamics of interpersonal relationships all play a role in determining the lifestyle, and thus housing preferences, of this demographic.

The Nature of Roommates

The pressures of housing unaffordability have led many American adults to living arrangements with strangers. Living with roommates is a common occurrence, with 30% of American adults between the ages of 23 and 65 living with roommates despite the economic rebound since 2008. In fact, the proportion of adults living with roommates increased 9% from 2005 to 2018.

There is no shortage of roommate horror stories on the internet, with websites from Cosmopolitan to the Huffington Post full of hundreds of different accounts of roommate experiences. Though these tales are good for a decent laugh in a gossip magazine, the gross, privacy-invading, and emotionally draining experiences that come with living with a stranger undoubtedly reduce the quality of life in one’s home. After a long shift helping patients at a hospital, the last thing a middle-income nurse needs is to come home to a kitchen sink his roommate clogged with moldy bread. Living with strangers can even prove to be treacherous; violent roommates can make cohabitation outright dangerous.

The quality and nature of one’s home is determined by the extent to which it allows for the quiet enjoyment of personal space. Everyone should have the right to comfortable, safe, and private living accommodations at a price they can afford. There is a common misconception that the rise of roommate living is a product of a generational desire to live life more communally: to find community in a world of late marriage, the isolation of remote work, and fluid relationships. In reality, many middle-income adults have roommates for economic reasons; they simply cannot afford comfort and privacy in their own home.

Annoying roommate habits actively dimmish the quality of one’s home life. Living with roommates should not have to be the default mode of urban living for middle-income individuals.

Living with roommates should be a lifestyle choice rather than an economic necessity. Small, stylish studio apartments provide an affordable alternative to doubling-up.

Age

Young professionals fresh out of college have a particular set of needs and wants that prioritize a well-located home over size or prestige. Being usually single and desiring the company of their general age cohort as they look to make friends and foster relationships, people between the ages of 20-35 look to live in dense, urban areas close to nightlife activities and ample transit options. In the Bay Area, these would include places like Uptown in Oakland and the Mission District in San Francisco.

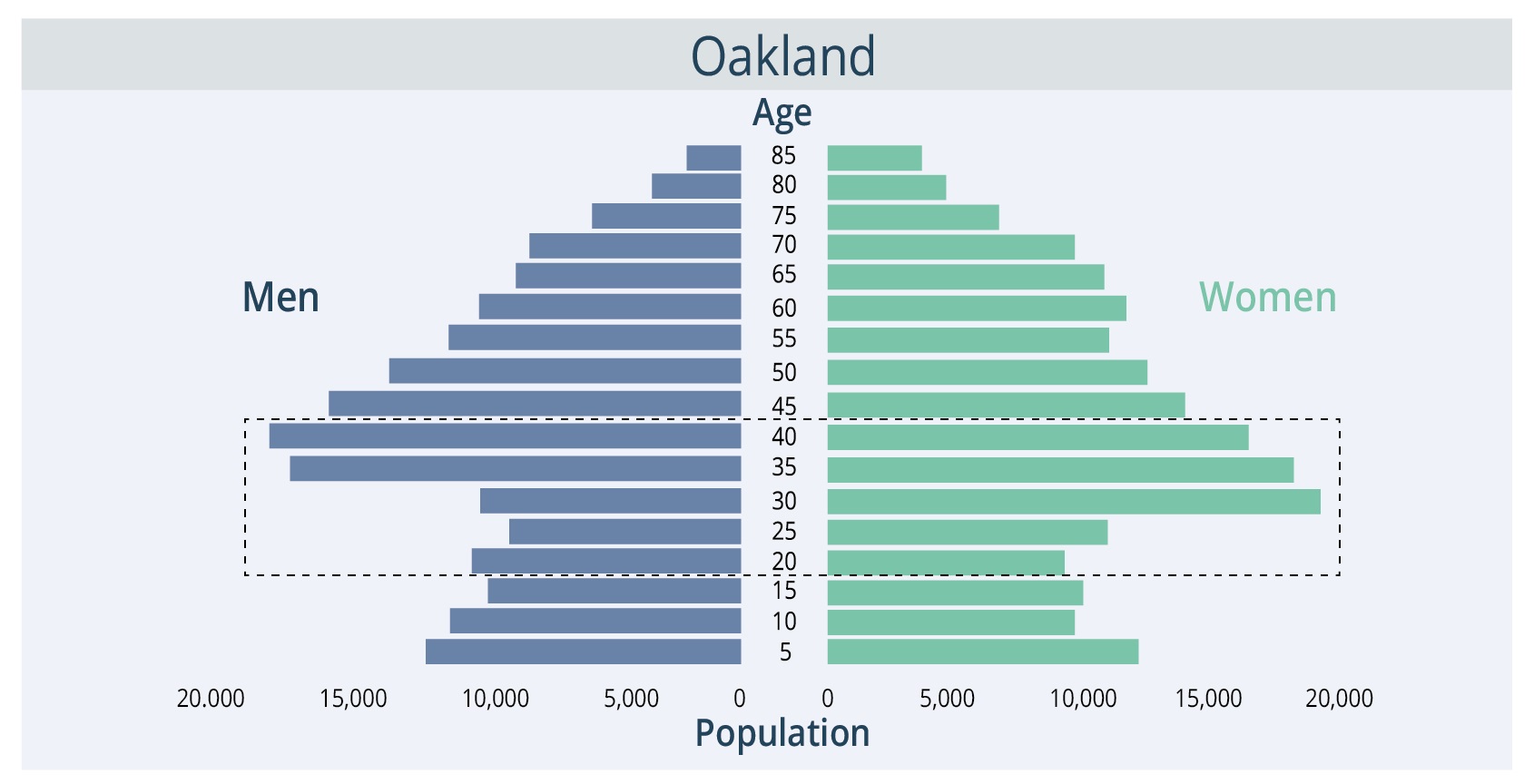

In Oakland alone, 1/3 of the population is between the age of 20 and 40. That is a population of over 143,000, with many in need of housing as they look to fly the nest and begin their careers in the city.

Oakland is not alone in having a large population of young folks. High-cost, productive metros across the country generally skew younger by sporting many young professionals and students. Young folks are attracted to these areas for their ample supply of interesting and engaging activities and, critically, a variety of career opportunities in fields they look to get involved in.

20 to 40-year olds make up a large portion of Oakland's population.

Source: World Population Review.

In our own portfolio, we cater to residents averaging 32 years of age. With an average income of $61K annually and an average credit score of 690, we see these tenants as a stable and reliable customer to cater to. We reject the notion that younger residents are financially volatile and difficult tenants, as appears to be the general sentiment of many property managers. Said differently, our target residents may have relatively modest incomes, but these incomes are very stable and make for a low-risk tenant base. A reliable income and high credit score make this customer base a safe and sage market for urban workforce housing.

From Seattle to Boston, young professionals are seeking opportunity in cities. Still single and making a median income as they begin their careers, young urbanites need quality, affordable housing that fits their urban lifestyle.

Relationships and Family

Many members of the urban workforce are Millennials, a generation marked by the lowest marriage rates of current generational cohorts. Much of this trend is driven by the desire to be economically stable and confident in individual social and career aspirations before committing to a single partner. This results in a substantial number of 25- to 34-year-olds living in single-individual households as they wait for the right time to tie the knot.

A person’s spatial needs are determined almost entirely by the size and structure of their household. It is much more comfortable to raise children in a three-bedroom apartment than in a one-bedroom unit. But for a single householder with no children or live-in partner, what ultimately amounts to a single room with an associated bathroom is perfectly sized for the householder. As Millennials spend more of their lives single, they do not have the same housing needs as their parents or grandparents had at their age until much later in life.

Without children or a partner in the house, it makes little sense for a single tenant to pay for unnecessary space. Functional single-person homes look vastly different from homes considered ideal for couples, especially when the individual is the sole source of income in the household. As more people remain single for longer, there is a growing demand for housing that enables a comfortable, affordable, single lifestyle.

Cities have consistently failed to provide “right sized” housing for residents. From a family of four looking for a larger apartment to a single, middle-income individual seeking out a space they can afford without a roommate, cities are full of one- and two-bedroom units that do not work well for significant segments of the population. Urban workforce housing is an opportunity to fill a gap in the housing market for singles with minimal spatial needs at their life stage.

Location Preferences and Economic Trends

Global and US trends point to an increasing urban population, with over 80% of the US population presently living in urban areas. Seeing opportunity, employers are investing heavily in real estate in downtown cores. Despite adopting a broad work-from home policy for all employees in perpetuity, Twitter recently announced a major expansion into Downtown Oakland with a large office lease. Major tech companies have also made significant investments in downtown real estate during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such big bets on cities are no wonder: over 90% of GDP is produced by and 88% of jobs are located in cities. People, companies, institutions and capital are eager to take advantage of urban opportunity, fueling the continued growth and economic development of cities. In short, cities are where “things happen”, and people move to be close to where the economic and cultural action is. The trend toward continued urbanization shows little sign of ceasing any time soon: cities exist as economic hotbeds at the intersection of individual desire and organizational need.

As urban economies spur the development of new offices, cultural centers and entertainment venues, it is important to remember that not everyone touched by these developments will be a high-income software engineer or project manager. Facilities maintenance workers, baristas, shuttle drivers and line cooks will come to serve these new office spaces and the people who frequent them. As urban populations increase, opportunities for both high- and middle-income individuals will emerge. As new offices and homes are built for high-income employees, other industries such as hospitality, healthcare and transportation services will rise to meet the demand of those with a discretionary income. These industries will be staffed by an urban workforce, who will also need and deserve a place to live within their budget.

New urban developments in vibrant economies provide job opportunities for an urban workforce.

The baristas and bus drivers that make bustling downtowns and office campuses work have a right to live in the cities they work in. Teachers who staff the schools that lawyers and engineers send their kids to deserve a 16-minute commute rather than a 2-hour slog through traffic.

People join the urban workforce in pursuit of economic and social opportunity. Those opportunities are best found in cities, where a variety of jobs and a diversity of people allow the urban workforce to build its own wealth and make valuable social connections.

When a member of the urban workforce finds a job in a city, they should be able to just as easily find an affordable place to live in it. As urbanites with a moderate discretionary income, they will look to be close to transportation choice, cultural opportunity, and essential services. Urban workforce housing should provide them an affordable way to live in proximity to the things that matter to them and make their lives better.

Equity

“Urban air makes you free” is a German saying from the Middle Ages that rings true to this day. For hundreds of years, cities have been places for people seeking economic opportunity, social acceptance, and new experiences. They have long provided resources and opportunities that smaller, homogenous communities simply cannot.

Unaffordable housing is a major limit to the accessibility of urban opportunity. Without an adequate and affordable home close to employment, healthcare, and education opportunity, the benefits of urban life are limited to the higher rungs of the socioeconomic ladder. Especially for those who cannot afford private cars, access to transit is a major avenue to opportunity. Everyone deserves access to the resources, culture, and economic opportunity that cities afford residents, and attainable housing is the key to providing this.

By building enough housing to meet demand, cities can ensure that both long-time and new residents can find valuable access to opportunity. Constrained housing supply in high-growth areas leads to rising market rents for existing units, elevating the required eligible income to live in a community. If an older couple is looking to downsize from a house to a one-bedroom apartment, they may find that they cannot afford the rent for such a layout in their city. Just as tragic, the children of longtime residents may not be able to afford to live in the very neighborhoods they grew up in.

Walkable, transit-rich, and amenity-rich neighborhoods should be available to all who wish to live in them. This goes for new arrivals in cities as well as long-time residents looking to change their housing situation but stay in their community. By placing accessible housing in such high-resource areas, the benefits of city life can reach a greater number of people. To ensure that opportunity truly exists for everyone, it is critical to make well-sited housing affordable and accessible to all.

Conclusion: Micro-living for the Masses

Middle-income individuals in the urban workforce are increasingly young, single, and urban. The lifestyles they lead generally demand comfortable, affordable, and well-located living spaces. A single lifestyle does not place a premium on space, so to enable affordability the size of the unit can be reduced without compromising any of the other aspects that make micro studios appealing.

Clearly, micro studios as an asset class are attractive to the young, single members of the urban workforce.