The Bay Area and similar urban markets require a solution that serves essential professional residents. Our cities need urban workforce housing: an emerging asset class that offers a market-based solution to the middle-income housing crunch. With scalable, moderate-density forms of housing that can fit into existing neighborhoods, recent approaches to urban workforce housing provide a quality product at an affordable price for working professionals.

The Shortfall

The housing crisis is unfortunately nothing new in the Bay Area. Since the era of the freeway revolts in the 1950s, a potent combination of social, political, and economic factors have prevented the metro area from approving and supplying a sufficient amount of housing to keep up with a growing population. A general aversion to growth and development ensured that housing supply remained stable while the population of the Bay Area increased substantially with the rise of the tech-fueled economy. In addition, property tax policy incentivized cities to value commercial development over housing development, and increasing construction costs made the construction of any structure absurdly expensive.

Due to the associated difficulties of building it, housing has been chronically undersupplied in the Bay Area for decades. According to urban policy thinktank SPUR, the Bay Area has seen a 699,000 housing unit production shortfall for the last 20 years. By 2070, an additional 1.5 million homes will need to be brought online to serve the region’s population and alleviate the crippling housing shortage.

With a total of 2.2 million units needing to be built by 2070, we estimate the price tag for this massive surge of development at $1.3 trillion at current construction costs. Such a price tag demands capital that public subsidy alone cannot hope to fully provide. To adequately address the scale of the housing deficit, it is crucial for private industry and capital to play a lead role in its development. Profitability and predictability are the keys to attracting needed capital for development, and as an industry we must identify and enable profitable, predictable solutions to the middle-income housing crisis.

The Underserved Modern Middle

In today’s economic landscape, it is often easy to forget that much of modern America was built on the presumption of the family household. For a long time, households making around 100% of the area median income could afford to live comfortably with all the necessities and some luxuries within their budget.

With so many reports of the disappearing middle class, it may seem that the socioeconomic rung no longer exists. Although the proportion of middle-income households has decreased over time, these households still make up a substantial portion of the urban population and still demand housing.

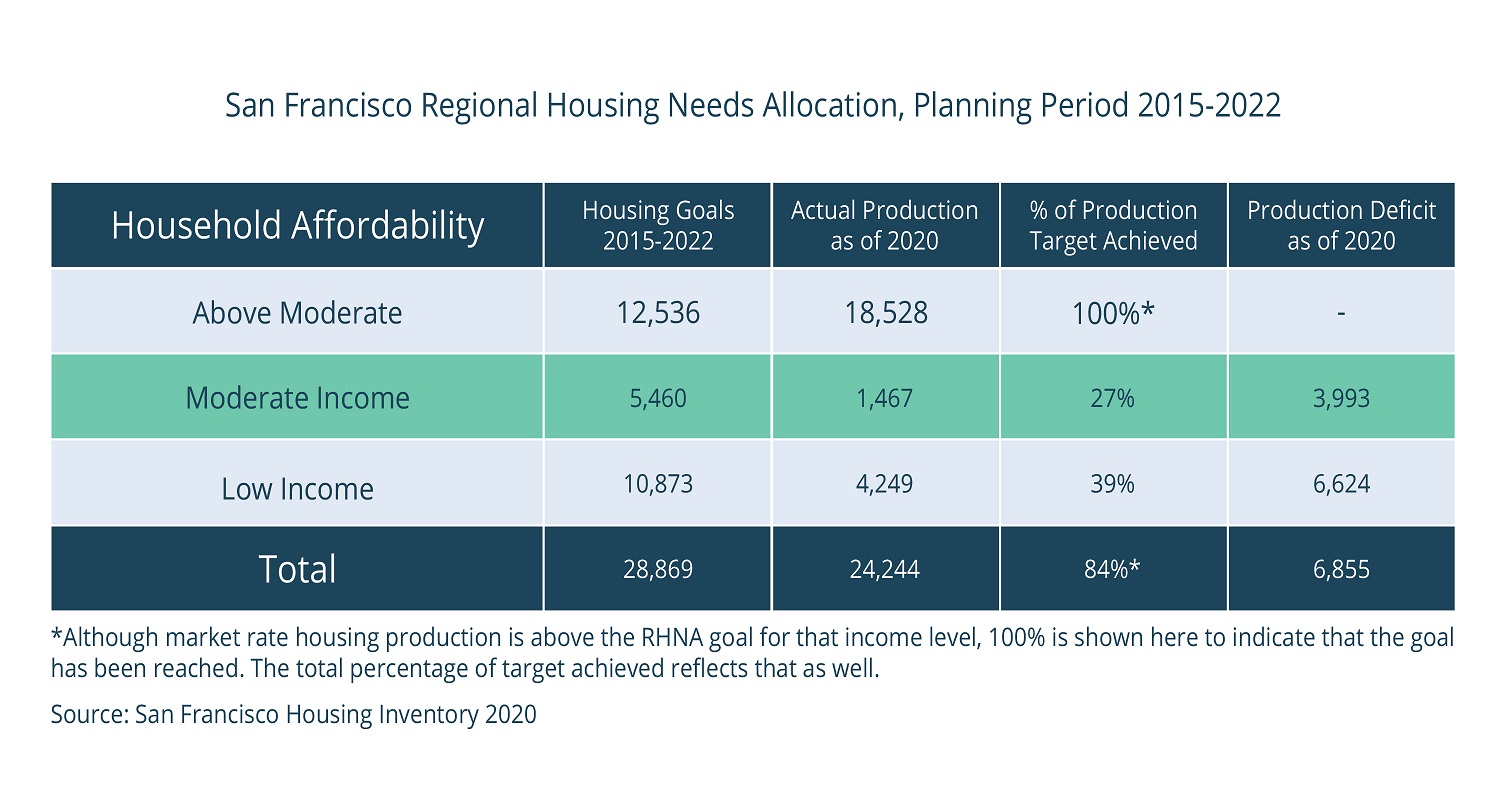

In 2015, the City of San Francisco anticipated that 19% of all new housing stock produced until 2022 would need to serve the middle-income level. This estimate was determined through the standard RHNA methodology for that planning period. But by 2020, the city achieved only 27% of this goal. Low-income and high-income units were produced at a higher rate than moderate income units, despite middle-income housing serving a stable demographic with a disposable income and evident demand for housing.

Even worse, the RHNA process may underestimate true housing needs. According to one report, the RHNA methodology underestimates the actual housing needs of municipalities by focusing on demographic projections rather than market indicators and realities. It is very possible that the RHNA political process is assigning municipalities fewer middle-income units than the market actually demands, making this shortfall particularly egregious. By the end of the 2015-2022 planning period, moderate income units are on track to be the least produced housing type in the city.

Moderate income units are on track to be the least produced housing type in the City of San Francisco, missing the production goal by the most out of all housing affordability levels. This is true for many Bay Area cities, including Oakland.

This housing production deficiency is indicative of a trend across the Bay Area, and adds up to a huge, untapped opportunity for solution-oriented capital. SPUR’s goal of a total of 2.2 million housing units requires the Bay Area to provide about 45,000 units per year until 2070 to keep pace with demand. It is not possible to achieve the Bay Area’s housing goals by building housing affordable only to those making low incomes and super high incomes. Digging from both sides of the mountain will accomplish nothing if policy and industry leaves a substantial piece in the middle.

The Wrong Kind of Housing

Perpetuating single-family zoning has been the default policy of American urban planning for almost a century, even in high-value urban metros. In the Bay Area, 82% of residential land is zoned single-family. This particular housing type works well for upper-middle class families with children and cars, but its low density and high price point excludes most members of the urban workforce.

82% of residential land is zoned single-family in the Bay Area. This drastically limits housing options in the region.

With gross under delivery of housing in competative geographies, middle-income housing is missing in high-value and high price urban markets. SPUR estimates that by 2070, the Bay Area will need to produce 269,000 units of housing within the price range of households making between $99K and $148K annually. Limited by the cost of construction and the lack of public subsidy, such a goal will be impossible to achieve without developers and investors moving to produce innovative forms of housing rapidly and at scale.

The housing shortage has made rent in the Bay Area prohibitively expensive for many residents. With a pre-pandemic median rent of over $3,720 for a one bedroom in San Francisco, many median-income earning singles have little choice but to “double up” with roommates to afford rent.

In response to the proliferation of roommate living, there has been a recent rise in co-living models – like Common – which create a more formalized system of living with strangers. Through shared spaces, staffed cleaning service, and community events, coliving claims to be an affordable, community-centric way to house young professionals in in-demand urban markets.

Coliving falsely accepts the premise that one needs to live with roommates to afford housing. Doubling-up is a symptom of rents being unaffordable to individual tenants, not a solution. Living with others should be an option for members of the urban workforce who seek the company of their peers, but it should not be the default mode of affordable living. To move beyond the formalization of roommate accommodations, there needs to be a new model of urban workforce housing that can achieve comfort, style, privacy, and location at a price affordable to the urban workforce.

A New Kind of Missing Middle Housing

A stark undersupply of housing is clearly the cause of the housing crisis, and the solution to the problem is to build more housing accessible to more people. Where this housing should be developed is also clear: within existing neighborhoods in highly resourced cities. SPUR’s Regional Strategy outlines a vision for densifying high-resource, low density parts of existing urban areas, both in downtowns and outlying areas. Rather than building in greenfields and perpetuating sprawl and unsustainable land consumption, urbanists believe that neighborhoods can be retrofitted with higher-density housing typologies.

A common objection to this proposal is that densification of historically low-density neighborhoods will be a detriment to the community’s character. There is a frequent fear of “Manhattanization” in California; a fear that densification inherently means the introduction of tall buildings in quiet, single-family neighborhoods. The idea of densification frequently conjures images of on-street parking shortages, crowded sidewalks, and shade cast by new skyscrapers.

Densification does not necessarily mean “Manhattanization”.

Such fears of denser neighborhoods are unfounded. In truth, many desirable Bay Area neighborhoods are already examples of dense communities that retain a single-family neighborhood feeling. This balance of density and community character is accomplished through what architect and urbanist Daniel Parolek has called “Missing Middle Housing.”

Defined as “House-scale buildings with multiple units in walkable neighborhoods,” Parolek’s model took the world of urbanism by storm as a crucial means of tackling the crisis of housing unaffordability in low-density neighborhoods. Duplexes, triplexes, bungalow courts and fourplexes are all more affordable forms of housing accessible to a variety of people when compared to conventional single-family homes. Best of all, they are also contextually appropriate in existing, walkable but low-density neighborhoods. Missing Middle Housing provides a way to maintain neighborhood character while making the areas accessible and affordable to more people.

Urban workforce housing’s necessarily compact unit size can fit into a variety of housing shapes and sizes, including Missing Middle typologies. From mid-rise complexes in downtown cores to townhome-style units in historically low-density neighborhoods, this asset class’s small unit size allows for a flexible model that can fit units into contextually-appropriate building typologies. As a model of flexible, affordable housing, urban workforce housing can be an effective tool for cities seeking to build high-density affordable housing in existing neighborhoods while remaining sensitive to the area’s context and character.

SPUR’s New Civic Vision outlines a need for 282,000 small apartment buildings to be built across the Bay Area. A substantial portion of these developments must be in high-resourced, existing neighborhoods to provide access to opportunity for middle-income individuals. With small unit sizes and a variety of housing typologies, urban workforce housing is in a unique position to help meet this need for middle-income individuals.

An urban workforce housing complex in a lower-density neighborhood. Urban workforce housing can blend well into the context of existing neighborhoods.

Conclusion

The Bay Area has chronically underbuilt housing for decades, leading to a severe shortage of adequate housing at all levels. The housing industry serves the luxury, middle-income and low-income markets, but it does not serve each proportionally. Luxury and affordable housing are built at higher rates than middle-income housing, leaving a substantial, underserved market despite demonstrated demand from the demographic. This has produced a particularly acute housing shortage for middle income individuals.

To fully tackle the severity of the Bay Area housing crisis, the region needs to tailor its housing production to each portion of the unaddressed market. Policy and industry must therefore be more attentive to the needs of the moderate-income urban workforce and provide adequate housing through a new kind of asset class: urban workforce housing.

With offerings in this asset class designed specifically for the demographic’s price point and lifestyle need, urban workforce housing is a critical piece of any strategy for housing the region. Political leaders, investors and urbanists should embrace the opportunity this asset class provides as another tool for making the Bay Area an accessible place for all.